Analysis by Sam Dudley

Edited by Alyx Jones

This is the first in a series of articles discussing the nature of themes in video game music. We’ll be looking at what makes thematic content in video games different to that of other mediums, with in depth explorations into some well known concepts and pieces from vgm history.

This month we’ll be exploring how and why themes evolve and just what makes them so ‘evolve-able’ in the first place, by digging into the ‘Prelude’ theme from Final Fantasy.

Birth of a Theme/Early Years (I-III)

Prelude has been through a number of variations and composer pass-downs in its 30 year history, but it all starts with Final Fantasy musical granddaddy Nobuo Uematsu and a humble pulse wave. Aside from being a lesson in simple yet effective thematic writing, Uematsu’s Prelude also has one of the most efficient time-spent-composing to historical-legacy ratios in video game music history. Producer Hironobu Sakaguchi gave Uematsu just 30 minutes to come up with the theme for FFI‘s opening screen. [redbullacademymusic.com 2014]. So how did Uematsu manage to write something so timeless in no time at all?

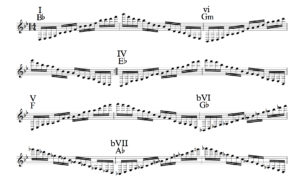

Prelude is written in the key of Bb major and mostly consists of a set of arpeggiated chords known collectively as the ’50s progression (ubiquitous in ’50s/’60s pop music, but also pops up in classical music as far back as the 17th century). By adopting this classic progression Uematsu harks back to a wealth of timeless music, and as a result this quality rubs off on Prelude itself. The arpeggiated chords seem to stretch out into infinity and the addition of a short delay effect compounds this sense of hefty, important legacy. Our composer says a lot with very little by using his tools effectively. At this point, Prelude manages to be a characterful piece of music and at the same time, a bit of a blank canvas, and this is what makes it a good theme. There is a core personality to it, but there is also scope to develop it. As we will see down the line, Uematsu and other later composers make great use of these possibilities.

Sonically, not much changes between I–III’s Preludes aside from a key change to C major from II onward (something that remains relatively unaltered throughout the series). Perhaps Uematsu was keen to have a musical anchor while the franchise found its footing. He didn’t rest on his laurels for long mind…

Age of Harmony (IV-VII)

At this point in the series, Prelude was still the sound of one lonesome square wave going up and down. Enter: SNES. A shiny new console, with shiny new sound capabilities, and a shiny new FF title to be made. Our intrepid composer must have been inspired.

In Final Fantasy IV Prelude goes through its first major transformation: orchestration. It begins with one round of what I like to call the h-arpeggio, and then on the repeat the ‘orchestra’ makes its grand introduction, establishing a sound that will stay with Prelude for the rest of the series. Uematsu’s predominantly string harmony sticks to the chords of the arpeggio line; the basses play the root notes, cellos and violas in thirds and fifths on top etc. Nothing flashy. But what his harmony does is greatly enhance the emotional weight of that arpeggio line. The sound is bigger, the feels are amplified. He also includes a simple melody in the woodwinds which gives the whole arrangement an added sense of direction. Plus, we can hear the string section shifting with short counter-melodies, adding to the perception of motion. It is quite a musical hole-in-one.

IV was both a critical and commercial success and was praised for expanding what RPGs were capable of. Through experience and experimenting we begin to see a franchise mature, and this is mirrored in Uematsu’s equally well received score. Prelude had also matured: What started life as a melancholic arpeggio was now, through orchestration and compositional techniques, developing into a full bodied orchestral theme.

Between IV-VII Uematsu gently tweaked the new Prelude sound including small changes to instrumentation. The melody in Final Fantasy VI is on flute played with little musical inflections giving it a folk-like feel, perhaps symbolising the main conflict in the story: rag tag rebels (folky flute), against the empire (regal sounding orchestra). In Final Fantasy VII, Uematsu expands Prelude’s orchestral palette with woodwinds and brass. Not long after VII though, change was in the air again.

Age of ‘OK, Maybe This Instead?’ (VIII-XV)

1997. Final Fantasy VIII began development and Square were keen to throw off the some of the well worn shackles of RPG conventionalism they helped establish with previous FF titles. The direction change was clear from the opening screen of the game: there’s no Prelude. Instead Uematsu serves up some orchestral pomp with ‘Overture’.

This is the first of a number of changes for Prelude. From VIII onward we start to see a shift in how the piece appears in the series. In VIII and Final Fantasy IX specifically, Prelude no longer introduces us to the story but instead is first heard at the end of your story, or rather when you get a game over screen, and it’s here that Uematsu treats us to his next variation trick: tonality change. At the end of VIII‘s ‘The Loser’ we hear the familiar harpeggio and the 50s progression, but on the repeat Uematsu changes the opening Bb major to Bb minor. With this seemingly minor change the character of Prelude has been altered. No longer is it the nostalgic precursor to your epic journey, it is instead the sound of your failure. IX‘s game over version of Prelude has a more straightforward change; simply using piano instead of harp. Things start to get more interesting during the final chapter of the game when we hear the piece ‘Crystal World’. Here, Uematsu really starts to stretch his source material.

In ‘Crystal World’ we recognise that familiar harpeggio and rhythm, but something sinister is going on with the chords. They follow a similar shape to the Prelude we know and love but the key is now loosely based in C minor and all the chords are minor, giving us a fearful, evil sound. Because not all the chords fit into the implied C minor key any sense of balance is removed, our musical footing unsure. The last little touch to really ensure our displacement is the arpeggio coming back down on the descent is played in reverse; a very eerie sound.

These variations are really important to Prelude’s legacy as they are great examples of how the piece is not just the introduction to a new story, but that it is intimately woven into the fabric of the FF universe. The series has always had recurring design elements like symbols, bestiaries, and characters (kupo!), it is a great way of adding another layer of emotional investment for the player. Uematsu does the same thing: by using this recurring thematic content he reminds us of something beyond the music itself. This is basically the crux of the idea of themes in media, to point to something beyond the object of the theme.

In these variations Uematsu’s tweaks are subtle yet effective. Now, we should probably talk about the musical sledgehammer that is Final Fantasy X‘s Prelude.

“I remember this arrangement was the result of being inspired by the visualization of the game scenes,” – musical director Kenji Kawamori. “A radio DJ appears right after the first scene where this song is played.” (Polygon.com 2016).

This time Uematsu gives our theme the genre swap treatment. What was once counterpoint and mezzo piano is now four on the floor and synth bass. It is the variation that stands out the most in my opinion, which is clearly the intention. Design-wise, X‘s future fantasy-scape is the antithesis to IX‘s nostalgia-fest. Uematsu uses the occasion to demonstrate his musical versatility whilst still keeping us grounded in the FF universe with the recognisable elements of his original Prelude theme.

After X, Uematsu starts to move away from the FF series but Prelude lives on. Final Fantasy XII composer Hitoshi Sakamoto wastes no time in putting his mark on the theme, giving us a “psyche!” moment in the opening cinematic with a completely different piece of music after establishing Prelude. Another composer keen to leave his imprint on the series, Masashi Hamauzu (Final Fantasy XIII‘s trilogy composer) does away with Prelude as an introductory piece entirely. Instead he favours to scatter hints of the harpeggio in the soundtrack itself (listen to ‘The Sunleth Waterscape’ and ‘Eclipse’). It is the last of the three new composers, Masayoshi Soken who restores Prelude to its former glory in the most grand orchestral iteration yet in Final Fantasy XIV: Realm Reborn. Be sure to lookup his Discoveries version where he serves up some variation in the form of quicker tempo and alternative instrumentation.

Honourable Mentions

Prelude also has a rich history outside the main series of FF titles and beyond, including being used in a Japanese Toyota car advert, no less (further testimony to the universality of Uematsu’s theme). This produces some interesting results in the context of effective theme variation, and one worth noting in particular comes from the relatively obscure (in the west at least) FF Dimensions for mobile. The reason it stands out is composer Naoshi Mitzuta‘s bold decision to alter the harmony originally introduced back in IV in subtle ways with some alternative chord voicings and inversions. Like most of the previous Preludes, it is in the key of C major, but Mitzuta steers us onto a rather different course by adding close harmony in the form of major seven and suspended second chords; complex stuff compared to Uematsu’s original 50s progression. Further, the bass plays an inverted (i.e. notes other than the root note of the chord) progression. The end result of all this is a far dreamier, ambient Prelude. If you’re looking to switch up a theme in an interesting way, this is how you do it.

Summary

Uematsu’s Prelude is a great case study in thematic writing for video games. It goes through 25+ variations in its 30 year history with humble beginnings as a single arpeggio line up to Realm Reborn‘s grand orchestral metamorphosis and beyond. Along the way we’ve seen how Uematsu developed it through changes in tempo, key, harmony, and instrumentation, with other composers later on in the series breathing new life into the piece with further variations like alternative instrumentation, and buy viagra sildenafil chord voicings. It is a testimony to Uematsu’s compositional skills that Prelude has been able to become so malleable and still retain the original character that has seen it through all these years later. In a body of work stretching over 100s of tracks and many memorable compositions, Prelude stands out as one of Uematsu’s greatest themes for Final Fantasy.

References

Dwyer, N. (2014) Interview: Final Fantasy’s Nobuo Uematsu on Redbullmusicacademy.com http://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2014/10/nobuo-uematsu-interview

Corriea, A.R (2014). Spira Unplugged: Behind Final Fantasy 10 HD’s remastered soundtrack on Polygon.com. https://www.polygon.com/2014/3/18/5498016/final-fantasy-10-hd-remastered-soundtrack